Sam Mansfield grew up and attended college in New Hampshire. He is currently an MFA candidate in poetry at the University of Houston. His work has been published in Explosion-Proof Magazine.

Writing Space

Sam Mansfield

Sep 21, 2013

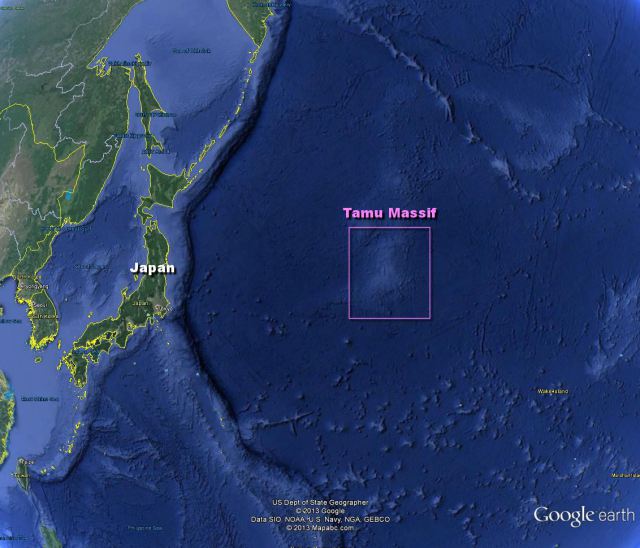

Space and place continue to be fertile territory for writers living around the world today. Why? We hardly know the space we live in. Just last month, scientists discovered

a volcano on the bottom of the Pacific Ocean more massive than any other volcano known on Earth.

How could we have missed this? We know about the volcanoes on, say, Mars. We even have detailed pictures of them.

It's possible we are so alienated from and ignorant of the space we inhabit because of the way we conceive of it. The way we relate to space is largely determined by our location and our culture. There is good evidence to show it is also strongly influenced by the language we speak. Since this blog is written in English, let's take a look at English for a minute. It's a fine, serviceable language. Like many elements of American culture, it doesn't ask us to think too much about where we are.

For example, the spatial frame of reference in English is not absolute, but relative. In other words, I can describe the location of my copy of the latest

Gulf Coast by relating it to other items on my coffee table:

It's just to the left of Bananagrams.

I don't have to refer to a fixed, overarching system. In fact, if you look more closely at my phrasing, the system I'm referring to is myself. What I'm actually saying is,

If you were sitting where I'm sitting, Gulf Coast would be on the side of Bananagrams that corresponds to the left side of your body.

Of course, I could give you the GPS coordinates describing the exact location of the literary journal. But I have a choice to say it in a more relative way.

This is not the case in many other languages. According to one text I'm reading for my sociolinguistics class, about one third of the world's languages use a spatial frame of reference that is absolute.

So, if I were speaking one of these languages, and I wanted to say where my copy of

Gulf Coast was, I might be forced to say,

It's just northwest of Bananagrams.

The implications are far-reaching. In order to speak one of these languages appropriately, I would have to constantly be aware of my position relative to the compass bearings. I'd have to maintain, in my mind, a bird's-eye-view of the world. That's a degree of spatial awareness English has never required of me.

Would I be better off, as someone trying to write about place, if it did?

Difficult to tell. I probably wouldn't get lost as often.

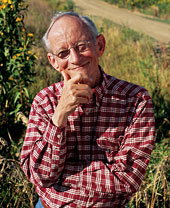

When it comes to writing about place, maybe the English language doesn't do us any favors. Nevertheless, plenty of writers have written about place, in English, with startling awareness and impressive sensitivity. One of them is Ted Kooser. You can see that awareness for yourself in his poem,

"Memory." An excerpt:

Spinning up dust and cornshucks

as it crossed the chalky, exhausted fields,

it sucked up into its heart

hot work, cold work, lunch buckets,

good horses, bad horses, their names

and the names of mules that were

better or worse than the horses,

then rattled the dented tin sides

of the threshing machine, shook

the manure spreader, cranked

the tractor's crank that broke

the uncle's arm, then swept on

through the windbreak, taking

the treehouse and dirty magazines,

turning its fury on the barn

where cows kicked over buckets

and the gray cat sat for a squirt

of thick milk in its whiskers [...]

Kooser's skill here lies in the incidental nature of his description. The main act of the poem is to describe an aspect of the mind--not to describe the place where he grew up. Yet, in the course of asserting that memory behaves in a certain way, Kooser provides to his reader unforgettable glimpses of a landscape with which we understand, by the end of the poem, he is intimately acquainted. As place poems go, this one's a double whammy.

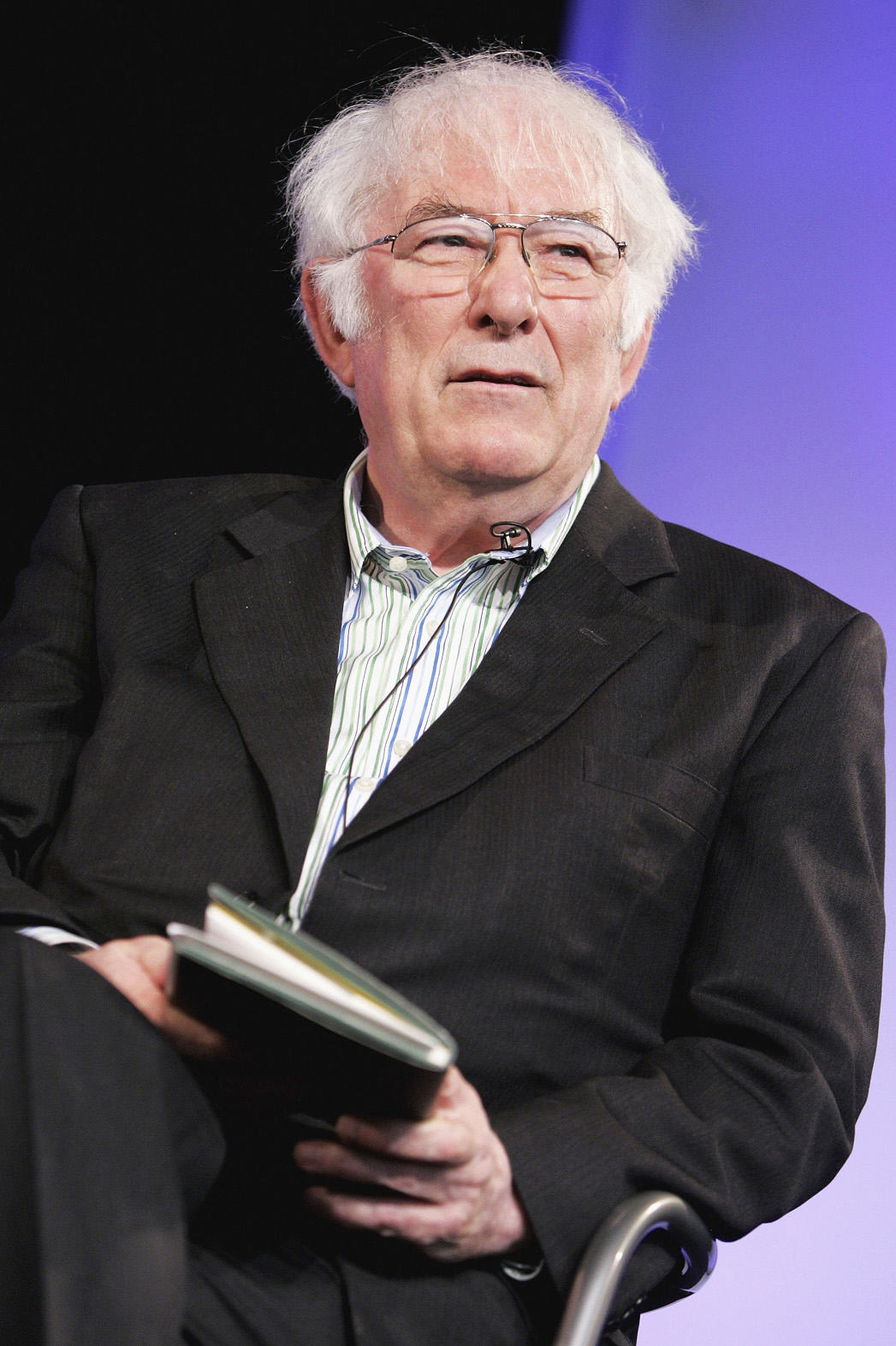

Capturing the spirit of a real place in words is no mean feat. Almost more impressive, to me, is the ability of a writer to vivify an imaginary place into being. Seamus Heaney took on this project in his poem,

"The Republic of Conscience." Here is how he opens the poem:

When I landed in the republic of conscience

it was so noiseless when the engine stopped

I could hear a curlew high above the runway.

At immigration the clerk was an old man

who produced a wallet from his homespun coat

and showed me a photograph of my grandfather.

The woman in customs asked me to declare

the words of our traditional cures and charms

to heal dumbness and avert the evil eye.

No porter. No interpreter. No taxi.

You carried what you had to and very soon

your symptoms of creeping privilege disappeared.

Why is this talent important?

Some might argue that it's all well and good to be able to imagine purely fictional places in great detail, but not particularly relevant. A distraction, even, from what really matters. Typically, what these people mean here is war zones. (It's a wonder no one's thought to write about those before.)

I think the ability to write plausibly and feelingly about entirely imaginary places is vitally important to our survival.

Adrienne Rich wrote, "For now, poetry has the capacity--in its own ways and by its own means--to remind us of something we are forbidden to see."

Living in the sprawling, polluted, contemporary American metropolis that is Houston, I can't help but agree with Rich: there is a better way of living that we are being prevented, by our historical circumstances and our own cultural paradigms, from visualizing. The best writing about place that can happen right now (at least in the U.S.) will work to resolve that deficiency in our imaginations.

How could we have missed this? We know about the volcanoes on, say, Mars. We even have detailed pictures of them.

It's possible we are so alienated from and ignorant of the space we inhabit because of the way we conceive of it. The way we relate to space is largely determined by our location and our culture. There is good evidence to show it is also strongly influenced by the language we speak. Since this blog is written in English, let's take a look at English for a minute. It's a fine, serviceable language. Like many elements of American culture, it doesn't ask us to think too much about where we are.

For example, the spatial frame of reference in English is not absolute, but relative. In other words, I can describe the location of my copy of the latest Gulf Coast by relating it to other items on my coffee table:

How could we have missed this? We know about the volcanoes on, say, Mars. We even have detailed pictures of them.

It's possible we are so alienated from and ignorant of the space we inhabit because of the way we conceive of it. The way we relate to space is largely determined by our location and our culture. There is good evidence to show it is also strongly influenced by the language we speak. Since this blog is written in English, let's take a look at English for a minute. It's a fine, serviceable language. Like many elements of American culture, it doesn't ask us to think too much about where we are.

For example, the spatial frame of reference in English is not absolute, but relative. In other words, I can describe the location of my copy of the latest Gulf Coast by relating it to other items on my coffee table:

Comments (0)

Add a Comment